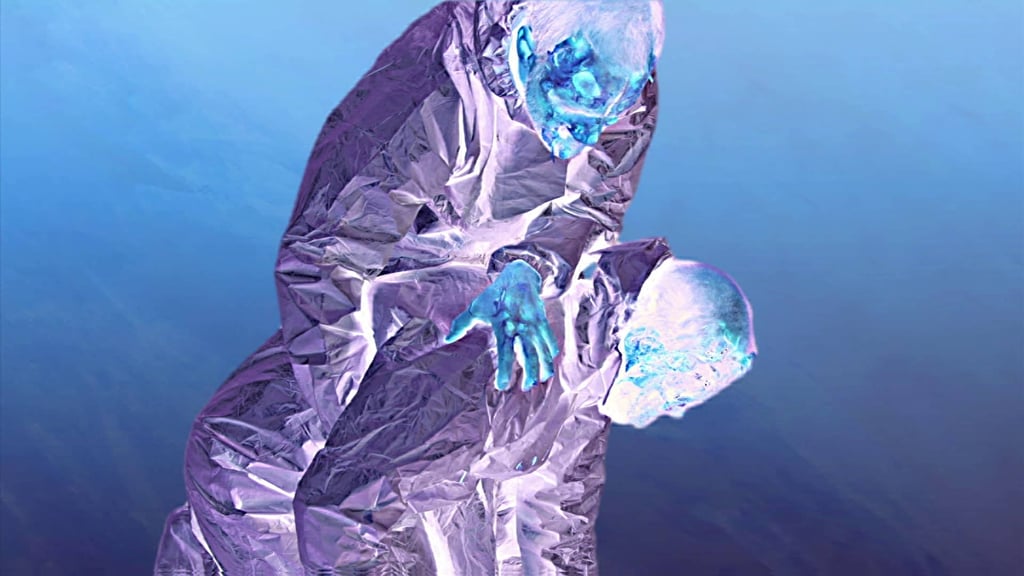

Dignity (2012) By James Fotopoulos

EFS PUBLICATIONSFILM REVIEW

Maximilian Le Cain

1/26/20243 min read

To tie in with the current retrospective on his work at Microscope Gallery, NY, I have decided to re-publish my review of his film Dignity, originally published in the pages of Experimental Conversations (Issue 12, Autumn, 2013). - Maximilian Le Cain, March 2015

There is a strong case to be made that James Fotopoulos is the greatest experimental filmmaker of his generation. More than any other I know of, his strength is in his vision. A much-abused word, to be sure, but one which Fotopoulos’ cinema redeems. Its constant task, ever since his first films in the mid-‘90s, is to repeatedly articulate a specific and unsettling set of relations between minds, bodies and objects suspended in a very particular tension. The objects, human and non-human alike, that Fotopoulos presents his viewers with in his typically ‘primitive’ fashion, at once crude and iconic, are viewed with a bizarre, almost extra-terrestrial detachment. The familiar becomes alarmingly alien, whether it is the ‘familiar’ of a domestic situation or a generic archetype- or of the body itself. This process draws its power from Fotopoulos’ concern with the most intimate and troubling of human experiences: pain. Physical, mental or spiritual: pain collapses these boundaries, just as it can wear down the distinctions that we have consciously or unconsciously relied upon to define ourselves as human, setting boundaries between ourselves and objects, between existing in a familiar state or discovering ourselves as unexpectedly porous when invaded by darkness and mystery. Pain eating away at our individuality, allowing for a vaster experience of existence even as it destroys us.

Dignity, the title of Fotopoulos’ excellent new feature film that premiered earlier this year at Locarno, is one of the first victims of this process. We lose the privilege of being able to designate absurdity; in our becoming absurd, the absurd becomes nightmarishly serious.

These mutations and sinister expansions provide both the form and content of Fotopoulos’ work. The objectivity of his vision is the objectivity of pain itself, regarding each image it encounters with the sort of detachment an alien might bring to its first vision of earth. Fotopoulos’ predilection for bald, stark, exclamatory images that present their subjects with the frontality of a child’s drawing (or a cave painting) strongly implies a rediscovery of the world, suddenly made new and strange. This impression is only heightened by the typically lingering pace of his shots that frequently follow each other with the dryly regular rhythm of items on a list. Audiences are confronted with elements of reality in such a way that they suddenly can’t take them (or their relationship with them) for granted any longer. They are revealed anew in the light of an inhuman fascination.

This should not to be mistaken for coldness; there is great emotional charge in the situations and phenomena Fotopoulos conjures. But our faculties for processing emotion are somehow reconfigured, as they might be by the attrition of pain. Fotopoulos’ films are invariably documents of obscure processes of transformation, fluctuating between natural phenomena and strange ritual. As his work progresses, the emphasis is increasingly on the latter with the sludgily organic giving way to a blatantly digital aesthetic and a crisp artificiality that somehow manages to retain the atmosphere of murkiness that has always pervaded his work.

Dignity is a perfect example of this recent style. Adopting the basic premise and iconography of a science fiction story, it feels on some level like a solemn game of science fiction that children might indulge in having been exposed to a particulalry disturbing film of that genre. The most troubling elements are heightened. The narrative pace is suspended to emphasise a fixation on certain unsettling aspects of the story, which have become abstracted. Naturalism is forgotten: the flat-voiced characters move like zombies through DIY sets, encountering monsters made from what look like household items. Enacted scenes are juxtaposed with sequences of drawings. Yet there is nothing playful in the tone of this film. Much of its first half follows the tortured heroes’ travails as prisoners on another planet, with strange, rubbery creatures growing in their bodies. (Many of Fotopoulos’ characters seem somehow imprisoned, either literally as in the 2004 masterpiece Esophagus, or in domestic situations or even in their bodies.) Once again, it seems to be the force of pain that imposes the radical artificiality of Fotopoulos’ approach and renders his blatantly crude style so conducive to profound unease. Yet this passage proves a transition into the truly mysterious as the characters regain their freedom, and the film builds to a hallucinatory peak of decidedly non-seamless, bargain-basement transcendence.

One of cinema’s great duties is to render the world unfamiliar, to cause the viewer to get lost and then find their way back to their perception of reality with an expanded sense of its possible scope. All too often, the film opts to do the opposite, providing an artificial site of familiarity that comforts the audience. (And this has nothing to do with the subject matter of the film: a brutal horror movie can be as guilty of this as the most saccharine light comedy.) No body of work is more single-mindedly relentless in its programme of defamiliarising the familiar than James Fotopoulos’. This is what makes him such an essential artist.

Maximilian Le Cain is a filmmaker and film critic living in Cork City, Ireland.