If only films could be projected directly onto our dreams

EFS PUBLICATIONSARTICLE

Nikola Gocić

1/26/20244 min read

There are directors who push the boundaries of what is considered the mainstream cinema. Then, there are experimenters who dare to go beyond that. And finally, there is Rouzbeh Rashidi – the Iranian-born, Dublin-based filmmaker whose modus operandi is based on the polemic Remodernist Film Manifesto (which is by no means set in stone).

The second to his last offering, Ten Years in the Sun is supposed to “help you remember to forget”, as the titular epigraph suggests. Does it really work that way? You bet it does! It makes you ignore (or at least revalue) everything you have previously seen, providing an experience like no other – odd, immersive, stupefying and distancing all at once. Not to mention you won’t look at raw steaks and strawberries the same way ever again.

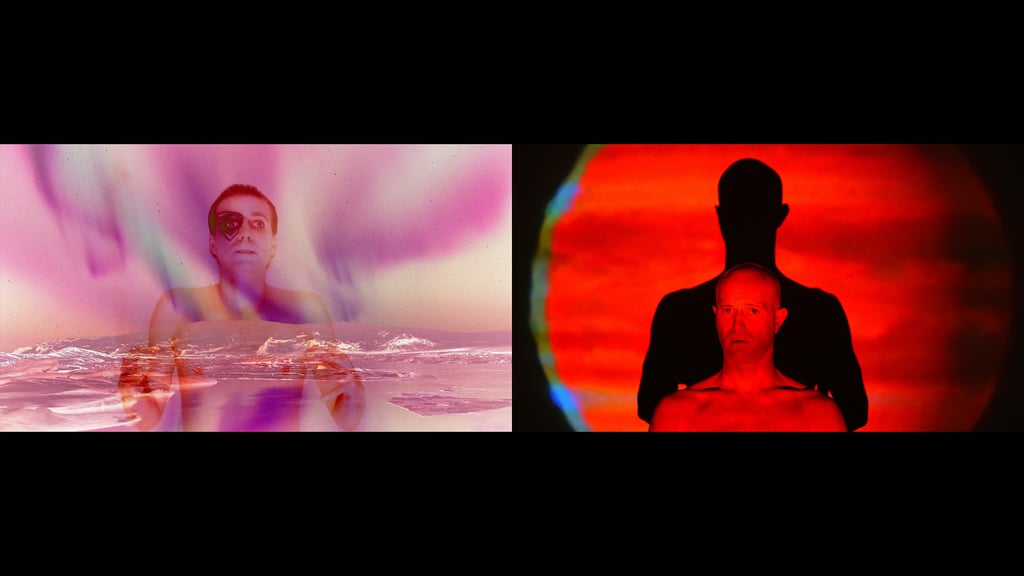

Opening with the series of flashing and glitchy images that would certainly trigger seizures for the people with photosensitive epilepsy, this ambiguous, rules-and-genre-defying extravaganza also reveals its creator’s gentle, melancholic side. The visually oppressive “prologue” is accompanied by a soothing piano piece which makes for the first of many deliberately jarring juxtapositions.

After a sudden cut, we see a man (Rashidi himself) walking through the grassy fields surrounded by fog. Seemingly unfazed by the ominous screeches coming from above, he turns around at one point when another “intrusion” introduces the film’s “cosmic” dimension. Someone or something alien with time, space and mind controlling abilities is about to wreak havoc on Earth… or maybe it is all just in a nonexistent hero’s head.

As you might have already guessed, there is no way to tell what (the hell) is going on, let alone summarize the bizarre happenings involving enigmatic, mostly silent characters (portrayed by the author’s friends) and rotating orbs which embody the above mentioned manipulative entity. (Scorpio is the one to blame.) Only a couple of “protagonists” speak and they meet in a ramshackle, dimly lit room to discuss the “antagonist” mentioned in the brackets and his “accomplice” Boris (the quotes stand for the assumption). That particular sequence oozes with Lynchian dread.

A paranoid, foreboding atmosphere is established, but that doesn’t stop the inspired and playful Rashidi from peppering the proceedings – the fragmented, stream-of-thoughts “narrative” – with a pinch of wry humor and tastefully done erotica (or rather porn) which perfectly fits the “private obsessions and perversions” part of the official synopsis. Intoxicating vignettes of varying content and oscillating quality could be extracted and remodeled as a wild bunch of miniatures, yet they are inseparable parts of an idiosyncratic, wonderfully chaotic whole which contains one of the sweetest sunsets ever captured on screen, as well as delicious superimpositions shrouded in unearthly sounds.

Both amusing and quite bemusing, Ten Years in the Sun is, essentially, everything you always wanted to know about the experimental “outsider” cinema, but were too afraid to ask. A work of creative lunacy, this soul-baring avant-garde poem channels the spirits of numerous, more or less obscure auteurs, yet it develops its own identity while coating the slices of human life with stuff the sublime nightmares are made of. To call it uncompromising would be an understatement.

The potential viewers are required to be as open-minded as possible and willing to dive deep into the vast sea of subconscious whose bottom is where the truths of existence lie. At first, it is hard to adjust to the violent tone and format swings (there are even a few shots reminiscent of Gust Van den Berghe’s Tondoscope), but once you realize the whimsical beauty thereof, you are in for a spicy challenge of epic proportions. Be warned, though – occasionally, it feels like the film watches you…

… which brings us to the artist’s latest effort – “a spectacular attraction” Trailers composed of the “pictures of a far-off world”, in his own words. You will not need any sunblock for it, but you will have to be more patient. Oneiric and onanistic, it takes you on a bumpy, three hour long ride through disorienting soundscapes, all the while pouring bold, frequently raunchy imagery filmed on Super 8, 16mm, 35mm and DSLR over you.

Once again, the tone and format change from one elusive segment to another, waking the weirdest of your inner weirdos – the one who wants to strip naked, put a corpse paint, rally to the streets and scream: “Akatsuki! Akatsukiiii!” (for the uninitiated, the latter words refer to the Serbian Dadaist Dragan Aleksić’s poem recited in Karpo Godina’s The Medusa Raft).

First-class irrationality (or maybe its exact opposite?) permeates the scenes of outré sexual rituals (pomegranates, anyone?) all locked in a vacuum of spiritual wet dreams. Even though the breast pumping is shied away from this time, the busty and curvy goddesses are very much present, posing in a catatonic stupor when not lashing their sex slaves in a sadomasochistic game. (Hey, are those the spheres from Ten Years in the Sun, making a cameo?)

The words are absent, either woven into the fabric of background noises or replaced by burlesque-like performances comparable to Marina Abramović’s endurance projects. Lost in a purgatory of crippling repetition, humanity is gazed upon from the position of a horny mysterious force which possesses the participants of the liberating and apocalyptic orgy on display. In order to grasp its meaning, you have to pretend to be a deity (if only for a while) and open your third eye growing on your forehead or even better, open another pair of eyes like those in Ken Russell’s Gothic.

Subverting the very nature of cinema and challenging “good taste”, Rashidi delivers an elliptical, hermetic phantasmagoria and, believe it or not, keeps moving the borders of filmmaking. He breaks the fourth wall in a peculiar fashion and creates an infectious illusion on the other side. Each of his canvases, whether drenched in psychedelic colors or draped in heavy shadows of neat imperfections, work as a swing of the pocket watch carried by that woman in the park, from this film’s demented masterpiece of a predecessor.

What we are treated to is more a reaction than action which produces a sensation of being stuck in an eternal moment, between invigorating light and sultry darkness of some abstract dimension.

Nikola Gocić is a film critic and writer of the blog NGboo Art.