Images On A Wire

EFS PUBLICATIONSARTICLE

Gianluca Pulsoni

1/26/20245 min read

Film, photography and national identity

Berwick Street Film Collective’s Ireland: Behind the Wire (1974) and Seamus Murphy’s The Republic (2016)

I

‘Knowing that if images were to survive economically, they now had to be sold as ambassadors of a nation, he nevertheless longed for that moment of silence, that illumination, that would not be sucked in by the breath of nationalism.’ These are the words of filmmaker Marc Karlin, taken from his A Dream from the Bath (1985).

For those who have never heard his name, Karlin is regarded as one of the most radical, pivotal and yet unknown figures of British cinema from the 70s to the '90s. He died in 1999, but his oeuvre has only recently been rediscovered. During the 70s, he was the founder and member of the Berwick Street Film Collective, a group whose films developed a combination of a militant approach and an experimental language. The groundbreaking Nightcleaners Part 1 (1972-1975) is most likely the best outcome of this experience. In 1974, the group had the occasion to release a film called Ireland: Behind the Wire (for those with access to the BFI platform, it can be viewed here), another example of their in-depth commitment to the idea of film as political expression.

The film deals with politics in Northern Ireland during the early 70s, years which saw an explosion of political violence as the situation there escalated into a national conflict. From today’s perspective, it is interesting to look at how this work depicted the Catholic struggle against Protestant discrimination, a struggle for gaining equal rights as well as recognition of a national identity.

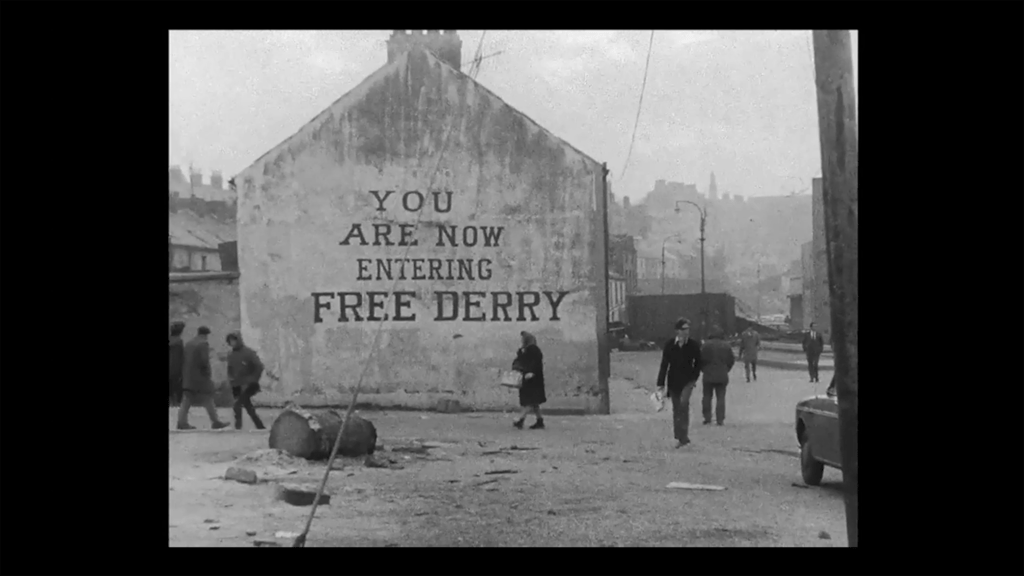

The voice-over sounds like it is shaping a long-form report. The tone is linear, but the narrative is in fragments, and the ending is open. We see and listen to interviews with locals, mainly activists, and scenes from daily life, with children playing and families having lunch or dinner. However, as soon as the camera discloses a wider context, the eye discovers the presence of the British army. It seems to be everywhere, while a series of vibrant protest marches spread out over many towns, from Derry to even London by the end. The film witnesses riots and beatings on the street, violence and death, true stories and social history. Graffiti, ads and protest signs also sometimes pop up as Brecht-like captions. “IRISHMEN DO NOT LIE DOWN UNDER ENGLAND”, “BREAK THE CONNECTION WITH ENGLAND”… The list is long.

The Collective was quite clear on their thesis behind the film, and the voice-over is explicit in assigning blame for the origin of the problems in Ireland: the British Government. Any process involving rights and self-determination in political terms is blocked and, therefore, passes through a fatal logic of opposition. From this point of view, the film’s approach seems coherent and admirable. Instead of focusing on visual symbolizations related to particular facts or narrowing the framework to a single city or subject, which would have made the political struggle in Northern Ireland appear out of context or peripheral to London, the Collective’s choice was to remain close to the intent of the protesters and to track down the dissemination of events inside and outside Northern Ireland in order to describe Irish identity and the ‘Troubles’ as open and international questions. In short, a non-illustrative approach that takes a documentary appearance and which can be read as a counter-narrative in which the images do not stand for a national language but serve a critical view. This is a counter-narrative made of fluxes and disjunctures, footage and photographs. It is a hybrid and fragile language whose name is cinema, a way to see private and public life sharing the same ‘scene’, a ‘scene’ whose name is history.

II

What is beyond the real and symbolic ‘wire’ that The Berwick Street Film Collective posed as the starting point for their observation and critique? ‘The other side’, the Irish Republic in that era and context.

Obviously, many things have changed since the 70s, but looking at Seamus Murphy’s latest publication, The Republic (here), a photography book dedicated to 100 years of the Irish Republic, one might say that something has remained unchanged, at least in terms of peculiar situations – scenes that one might see like the Joycean epiphanies that possibly make a country such as Ireland so unique – as the author remarks in the afterword of this book, talking about some specific pictures, their meaning and connection to his life and country.

For those who have never heard of him, Seamus Murphy is an Irish photographer and filmmaker, in other words, an artist who works through the visual texture of the world. He is known for being a war photographer, although his approach is far from traditional photojournalism, and as someone open to innovative, collaborative works with other artists, like an ongoing one with the ingenious British songwriter, musician and poet P. J. Harvey.

With The Republic one can appreciate a gaze able to look at moments as iconic monuments through a balance between intimacy and staging. Buildings, animals, barber shops, homes, pubs, museums, daily life, street life, boys, girls, men, women, old people, priests, politicians, natural settings, social settings, landscapes, abstractions… If it is possible to list some of the classes of subjects depicted in this book through a contemporary or timeless viewpoint, it is certainly impossible to reduce it to a canonical narrative. There is no attempt to tell a linear story through pictures, and the lack of text within the main body of the book emphasizes this impression. Nor is there any trace of opposite tendencies: a fixation on photography as painting or the presence of a ‘decisive moment’ as absolute belief or ‘ideology’. On the contrary, the variety of the formal compositions of each image and their juxtaposition/editing as a whole render a rhythm undoubtedly close to a polyphony. This is probably the only possible form to aspire to when dealing with a ‘wider picture’, and it is, therefore, something that we detect but that is not entirely visible. So, how do we proceed to decipher this project?

Reading some pieces written about this book, a set of similar terms seems to come to mind to describe the ultimate sense of its approach, terms like ‘portrait’ or ‘portrays’. ‘This book is a portrait of Ireland’ or ‘Murphy portrays Ireland…’ or similar. Well, that much is true. Portraiture undoubtedly belongs to the ‘family resemblance’ (Wittgenstein) related to the visual image as reference, a set of terms shared by visual artists in photography as well as in painting and sculpture. Murphy’s work is no exception. However, this does not say everything about The Republic. It follows that if there is a portrait, a subject is implied, but if this subject is a very particular one, then the outcome must be conceived accordingly.

Taking inspiration from philosophy, one might suggest that we look at the aforementioned wider picture / particular subject as a culturally shaped idea rather than a portrait and therefore regard Murphy’s The Republic as a contemporary Platonist work of sorts, something in which a passionate idea of Republic in fieri turns out to be the ‘architecture’ that lets us perceive the entire collection of pictures as an appealing visual dissemination of its nuances. This leads us to recollect Plato’s theory of ideas at its finest, with modern roots and immanent clues, with our eyes – a wire – between the ‘One’ (the idea) and the ‘Many’ (the images).

There are some pictures and not others because there is a precise force at stake that leaves marks, marks that can be defined as ideals we have to look for – in people, venues, and situations.

Gianluca Pulsoni

contributing writer at il manifesto