Open Night Cinema

EFS PUBLICATIONSREVIEW

Dean Kavanagh

1/26/20242 min read

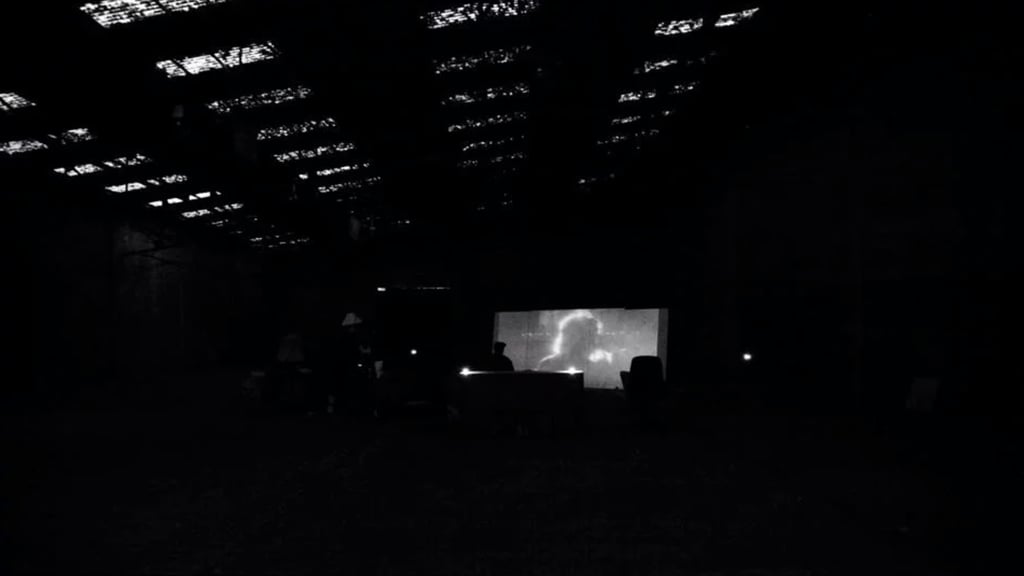

Open Night Cinema took place on Friday June 12th, 2015. It was a very special and intimate evening at a derelict industrial site. The space itself was vast and overwhelming, punctuated with patches of light and a tepid scent of chiselled stone. Watching people enter the complex through the overgrown exterior seemed to be a commingling of imagery from The Niklashausen Journey and Stalker. The atmosphere inside was completely unique and exceeded expectations; even Higgins and Roche somehow offset the fact that we might not leave in one piece. This was the unique flavour of the event, the taste of the unknown and, installed within it, a communal sense of circus, a sort of ‘professional mischief’. There was something quite assertive but also very delicate about the environment, like discovering a large ancient object in the midst of a forest that is about to be felled. Places such as this are home for filmmaker Michael Higgins, who thrives in the debris, a collector of disused and industrial artefacts. With his filmmaking, he connects the discarded to the ancient, or at least his vision of it. Suitably enough, this was a presentation of cinema as a traditional or indigenous ritual, perhaps with respect to some deceased tribe.

Once dark, the spoken word and electronics rippled deep into the space where they were held with a delicate and natural sustain before slipping away. While Cillian Roche’s performance of John Moriarty’s Stone Boat seemed to establish a current through the selectively lit environment, a brief but controlled vocal performance by Andrea Murphy fully mapped the true acoustic potential of the cavernous space. Beyond its visual and sonic compatibility, Roche’s performance was a perfect thematic introduction to Higgins’ feature At One Fell Swoop, which also stars Roche and was filmed at a sculptors’ community in Leitrim last year. A favourite moment in the live performance was when Roche discarded his tools, and as the sound drew back to the far walls, he followed, circled the audience in the dark, before reappearing in front of a wide projection screen; in effect, a 360-degree pan of the site. At one point, he sat with a small candle, and either by chance or calculation, his delicately lit distance from the screen transformed the clinging shadows on the white backdrop into a dusk-light maritime horizon, marooning him somewhere in time. After a short break, Higgins’ film starts up like a rollicking chainsaw, and we are all suspended like moths to the frightening draw of the white monolith of the screen, fully aware of our surroundings as the sound and light (and, indeed, the film itself) took new shape in the derelict site. Once it was finished, the eyes were burnt, the ears reassuringly lost, and the nose was rot with the alluring silt of pummelled rock. Apocalypse at its finest.